Genome editing:

A promising path toward

more sustainable agriculture

By Syngenta Group News Service

As the global farming community tackles the challenge of feeding the world’s booming population while reducing agriculture’s environmental impact, scientists and farmers see help arriving from an emerging technology: genome editing.

Genome editing, also known as gene editing, works with a plant’s own genetic variation and can either amplify or suppress the expression of particular characteristics in a precise way. The aim might be to improve the resulting food or enable the plant to better withstand pests, diseases or climate pressures. Or genome editing might be aimed at doing all of those things. The point is to work in harmony with a plant’s natural capabilities but improve them—just as traditional plant breeding has always done. Except much faster.

Because genome editing involves a technique that was discovered only recently—less than a decade ago—the agricultural benefits are only now emerging. Few foods developed through genome editing have hit the market, with the most notable exception being a genome-edited tomato introduced last year in Japan.

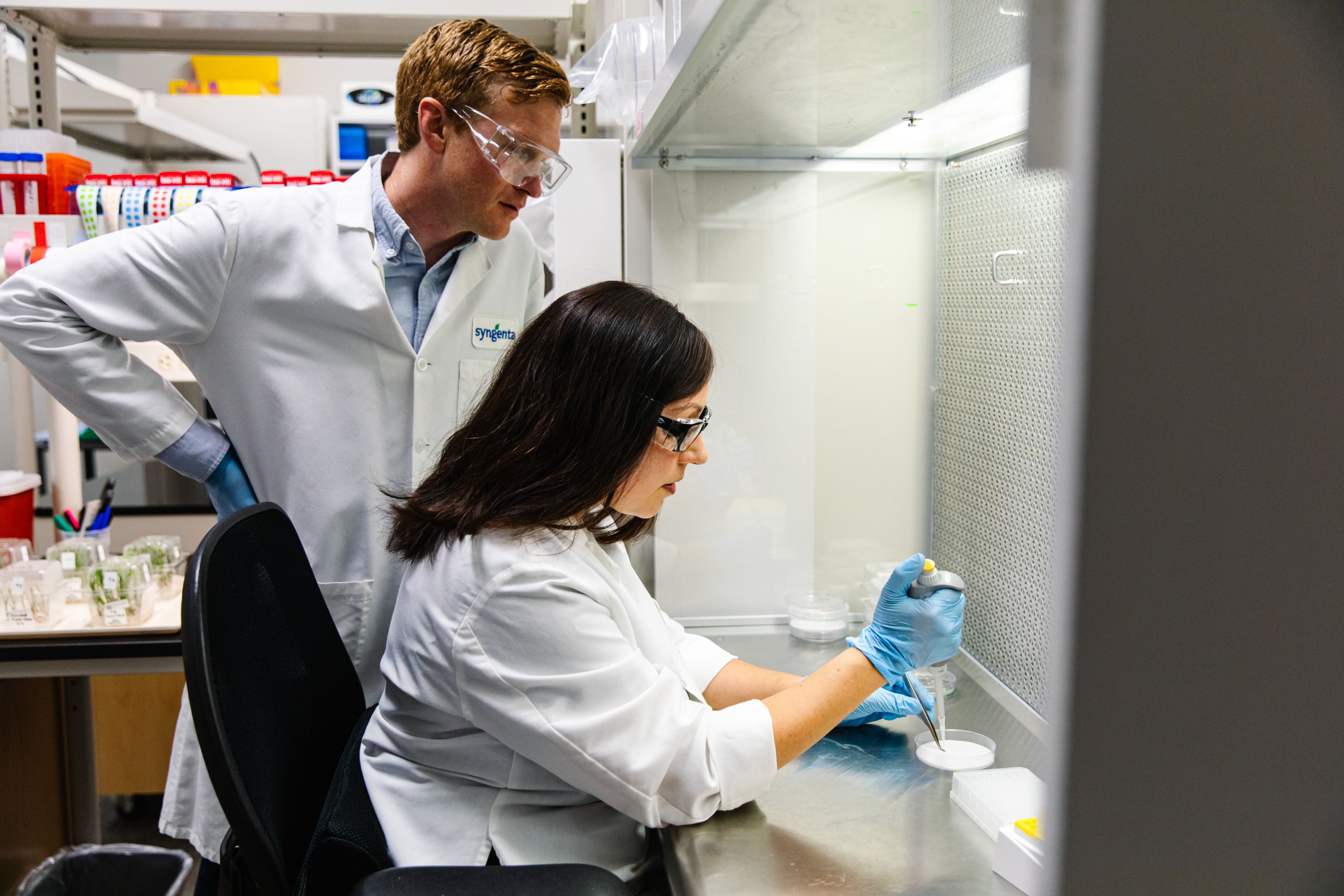

Jodi Avila, Trait Delivery Innovation Scientist, at work in the Syngenta Seeds lab in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA.

Jodi Avila, Trait Delivery Innovation Scientist, at work in the Syngenta Seeds lab in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA.

But researchers, farmers, environmental advocates and others have high hopes for genome editing—which could be used to develop fruits, vegetables, legumes and grains that have benefits such as higher nutritional content, longer shelf life, more resilience amid weather extremes and natural resistance to pests and diseases.

“If farmers have a crop plant that is more resilient to climate stresses and resistant to diseases, we will improve food security during global warming,” said Timothy Kelliher, Head of Technology Development for Syngenta Seeds. “We need genome editing. It’s a hugely important tool in the toolbox.”

Syngenta is not yet ready to publicly discuss its own product development pipeline, other than to indicate that the work is actively underway. But the increasing number of Syngenta patents related to genome editing attest to the company’s intention to be a leader in the field.

A departure from GMO technology

Genome editing is not the same thing as the more established, but often-maligned, GMO (genetically modified organisms) technology, where a gene from a different species is incorporated into a plant’s DNA. Genome editing allows for modifications using a plant’s own genes. The technique involves changing genetic base pairs within a plant’s own DNA, to reinforce a desirable characteristic or eliminate an undesirable one.

A useful everyday analogy is word-processing software. Genome editing allows the scientist to alter or eliminate base pairs—akin to changing a word in a sentence or punctuating it differently. That’s in contrast to the process with GMOs, which is analogous to dropping a sentence from a foreign language into the middle of a paragraph.

To be sure, GMO techniques, developed in the 1980s, have proven valuable to farmers and can greatly reduce the need for chemical crop protection. But despite a long track record of safety, GMOs have been widely misunderstood and become highly politicized. That has led to tighter regulations—particularly in the EU—and consumer skepticism in various countries that marketers of “natural” products often exploit.

Genome editing, by comparison, is based on a technique known as CRISPR (for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, and pronounced “crisper”) that is derived from naturally occurring genetic processes. The editing technique was developed in 2012 by Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, who won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work, as well as Feng Zhang at The Broad Institute and MIT.

“CRISPR was a huge scientific breakthrough,” Kelliher says.

Much of the early focus was on medical use of CRISPR science. Then, in 2019, Kelliher and his Syngenta colleagues in Research Triangle Park, N.C., invented a genome-editing technique for crops called “HI-Edit,” or “haploid induction editing,” that provides for an efficient method of editing commercial crop varieties.

Because genome editing does not introduce foreign DNA into a plant, and does not share GMOs’ four-decade history of polarized, politicized debate, many agronomists are optimistic that the regulatory environment will be much friendlier.

Timothy Kelliher: Head of Technology Development for Syngenta Seeds.

Timothy Kelliher: Head of Technology Development for Syngenta Seeds.

A race against new crop threats

Already, climate change is placing enormous pressure on farmers. Droughts, flooding and prolonged heat waves pose substantial risks to yields. And as weather patterns change, pests and diseases are migrating into regions that have not encountered them previously.

When it comes to developing seed traits that can withstand these pressures, time is of the essence.

“The field of plant breeding is very dynamic, as it involves various technologies from different disciplines,” said Uri Krieger, Head of Vegetables and Flowers R&D for Syngenta. “Plant breeding in general is a numbers game. The more products you can assess, the higher your chances to identify something you really like. Genome editing provides both precision and speed, which are both critical components to effectively develop innovative products that address customers’ ever-changing needs.”

With traditional plant breeding, it generally takes 15 to 20 years before a product with a new trait or traits comes to market. Using Syngenta’s HI-Edit, genome editing can shave 5 to 10 years off the process, Kelliher estimates.

Genome editing has the potential to reduce the need for fertilizers and pesticides, make farming more environmentally sustainable, produce vegetables that are tastier and help farmers achieve higher yields.

As Kelliher sees it, the benefits for consumers will also include vegetables with longer shelf lives and the knowledge that gene-edited produce will come from farm fields requiring fewer chemical interventions. For farmers, fewer chemicals can translate to lower costs, he says, while the gene-edited improvements should also mean higher yields.

Uri Krieger, left, Head of Vegetables and Flowers R&D, with Gusui Wu, Global Head of Seeds Research, right. Back center: Twan Groot, Cabbage Breeding Project Lead.

Uri Krieger, left, Head of Vegetables and Flowers R&D, with Gusui Wu, Global Head of Seeds Research, right. Back center: Twan Groot, Cabbage Breeding Project Lead.

Regulatory questions loom

Policymakers in the U.S., the EU and elsewhere are still determining how to regulate foods developed using genome editing. The Japanese tomato was approved with the blessing of that country’s regulators. But around the world, favorable regulatory conditions and expedited approval processes will be critical to the widespread introduction of such foods—and their potential to transform global agriculture into a more sustainable and productive system.

A 2022 article in the journal Nature Genetics found that the risks associated with genome-edited crops are “comparable to those of accepted, past and current breeding methods” and that the technology could prove especially beneficial to poor, smallholder farmers because it could accelerate the delivery of better crop plants to their fields. Consumers could also benefit, the article found, from crops that are nutritionally enhanced.

Kelliher and Avila in the Research Triangle Park lab.

Kelliher and Avila in the Research Triangle Park lab.

The article, however, found that failure to address the regulatory, legal and trade-related issues “squanders the potential benefits.” It concluded: “If the products of genome editing are instead regulated in the same way as transgenics [GMOs], then genome-edited crops may not reach farms in countries that adopt such policies, or in the countries that want to export foods to those markets; the research and varieties would be highly managed and controlled by multinational seed companies, and remain mostly unavailable to smallholder farmers in LMICs [low- and middle-income countries].”

An article published in the University of California Press’s Elementa journal described genome-editing techniques as “major biotechnology advancements that promise significant benefits within the agricultural sector.” It found, however, that there is “no national or international consensus on how to regulate” genome-edited foods, and that their future “will depend on interactions among complex social, scientific, environmental, economic and political factors, including how it is governed within and across nations.”

Shifting perspectives

The U.S. regulatory landscape is favorable to genome editing technology. In the EU, where GMOs are highly regulated, proponents of genome editing hope the newer technique will be viewed in a different light. So far, they are cautiously optimistic. After a drought-ridden European summer, a number of European lawmakers have spoken favorably about the potential of genome editing—and even GMOs—to protect the food supply amid the ravages of climate change.

Antonio Tajani, an Italian member of the European Parliament, has urged the EU to “liberalize the use of new assisted evolution technologies by untying them from GMO” rules, saying, “New agricultural biotechnology can provide experimentation for more drought- and pest-resistant plants.”

Charles Baxter, Head Global Seeds Development Traits & Regulatory at Syngenta Seeds

Charles Baxter, Head Global Seeds Development Traits & Regulatory at Syngenta Seeds

Charles Baxter, who leads trait development and regulatory affairs at Syngenta Seeds, said there’s “a much more favorable regulatory landscape” for genome editing than there was when GMOs were initially introduced. That’s “partly,’’ he said, “because of the excitement across the whole scientific community and the value chain about the potential of this technology.”

“Regulators have realized that this is something distinct from classical GMOs,’’ Baxter continued, “and they’ve also realized the safety concerns which existed about GMOs have never been realized. At the scientific level and at the level of the regulators, there's a real willingness to move ahead with this technology.’’