A bumpy ride:

How change drives a flagship farm

It’s a harvest day in early August at Elveden Farms. An early potato crop is being lifted. Onions are being laid on top of the soil for a few days before being taken in, a way to reduce drying costs and energy use. The main focus of this sizeable modern farm is root vegetables – potatoes, onions, carrots and parsnips – with a few fields of cereals.

The high-value root vegetables, potatoes and onions, go off to supply major food processors and retailers like McCain and McDonald’s, for which Elveden is a flagship farm. They also feed shoppers at major UK supermarket chains including Morrisons, Tesco and Sainsbury’s.

Huge changes have taken place at Elveden.

The crops have changed and so have practices.

They move the soil less and use less synthetic fertilizer.

Harvesting is done on a “just-in-time” basis

“You have to harvest when the customer wants the produce – and customer orders might change four or five times the day before you begin. You’ve got to be prepared to work almost every day,” says Andrew Francis, Farm Manager at Elveden Farms Ltd. He has been managing the land for 30 years and in that time, three separate farms have become one.We are in East Anglia in the UK. The area is known as Breckland, coming from the medieval term for “broken land”, which refers to the nutrient-deficient sandy soils.

Elveden is the largest ring-fenced arable farm in lowland Britain, meaning no part of it is rented or contracted out. It is part of Elveden Estate, a historic 22,500-acre (9,100 hectare) country estate owned by the Iveagh family. Around 10,000 acres (4,000 hectares) are farmland. Agriculture began here almost 100 years ago and the field layout is still the same with vast 100-acre (40 hectare) blocks. The estate runs several businesses alongside farming, including shops, restaurants, an inn, and holiday accommodation.

Is regenerative agriculture a “rebrand” of proven best practices like integrated farm management, integrated pest management, good soil management, good water management, good crop management and how they are all brought together?

Regenerative Agriculture means a whole farming system

About 4-5 years ago Andrew Francis first heard the term “regenerative agriculture”, yet he wonders if it is just another way of describing practices he uses all the time.

“If you’ve got all of those fundamentals right, then you’re 60-70% of the way to a regeneration system. You’re not thinking about individual crops, not thinking about individual years, but bringing it all together as a whole farming system,” he says.

On the Elveden farm, “It’s really about soil management and irrigation management, and how to bring those two together.”

“There’s a lot we can take from the past, then add the science, and that shows us how to move forward into the future.” – Andrew Francis

The goal is to leave the land in better condition

The farm is a highly successful but complex operation, because of its size, market pressures, and the effects of climate change. The need for change has been a constant in Francis’s 30 years and the pressure to evolve, to become more efficient, to leave the land in better condition than before never stops. And change, as he says, “can be a bumpy journey”.

Andrew Francis is a first-generation farmer, and sees himself as thinking differently, even disruptively, although he is conscious of the business’s long history.Commercial vegetable farming is a “high risk, low reward” business calling for sizeable capital investment and exposed to cost inflation, he explains. Climate change is a major worry. The area has hot summers, low rainfall and cold winters. Now there are extended dry periods, and he is concerned about high temperatures, water scarcity and increasing irrigation.

The day Syngenta Group met him, there had been no significant rain for 50 days. That means much more irrigation, with greater use of water resources and the irrigation teams working longer hours. When the temperature gets really high, they can’t keep up.

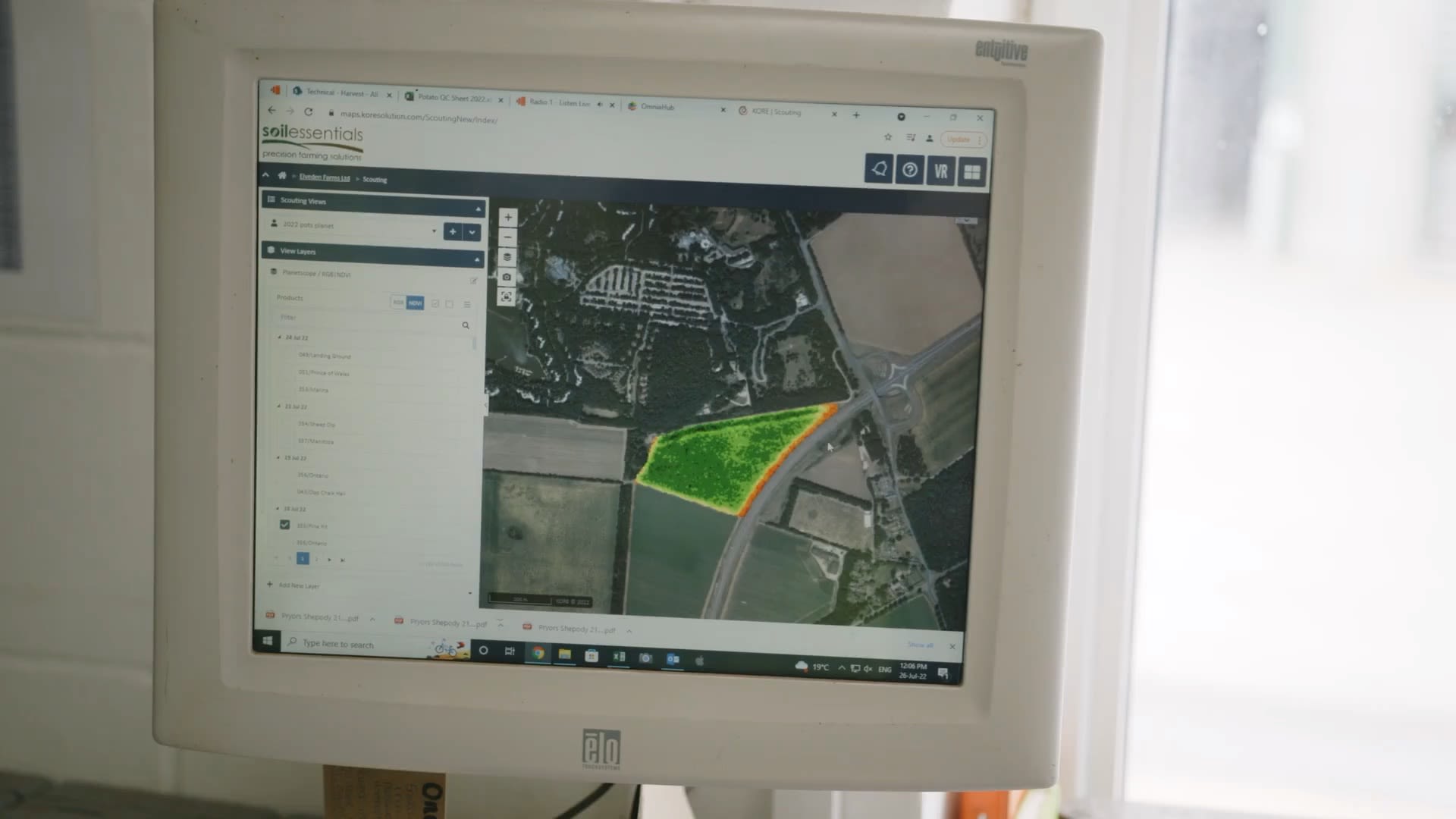

Productivity depends on detail, data and a deep understanding of the farm, from microclimates to each field’s weaknesses. Data is used extensively to make decisions.

Water-intensive crops may not be sustainable

So far, the farm has been able to sustain its high yields and good quality of root vegetables. Yet they might end up having to change the type of crops they grow. The lower-value root vegetable crops that need a lot of water – carrots and parsnips – might not be sustainable for much longer.

“We have to ask, do we grow crops that require lots and lots of water? Normally, we would be planting some cover crops while harvesting at this time of year. But the soil is too dry and the crops wouldn’t be able to germinate.”

Another challenge is water storage, but to store water, you need the rainfall in the first place. And the cost of the engineering for, say, large lagoons, could be prohibitive.

With all his experience of transformation, Francis is cautious about making changes too quickly without worked-out examples because of the potential downsides of some practices. One example he gives is cover crops which can encourage some pests, largely because UK farmers no longer have access to specific chemistry that would have controlled them. On the other hand, pollinator headlands have brought many benefits to Elveden.

Pollinator headlands around the edges of fields host predators that predate aphids – small sap-sucking insects – which are getting harder to control in commercial crops.

Advancing agriculture means evaluating outcomes

For any change farmers make, they need to know the economics. One of the ways to do that is through trials, which is why Elveden is running an innovation field in partnership with Syngenta. “We’re trying to work on what the net outcome would be, which is really important,” Andrew Francis says.

“As farmers we have to take all the different problems and components and bring them all together into a system or solution. Quite often that means we have to compromise some of our ideals to make things fit together. It’s about using and evaluating applied knowledge to come up with the outcome.”

Pollinator headlands benefit soil and productivity

Both biodiversity and farming output have benefited from pollinator headlands around field perimeters. The headlands, soak up run-off and fertilizer and maintain good soil structure, avoiding compaction.

The areas provide habitats for around 130 different species, including 8 which are rare in the UK ; recent studies show up to 1,200 individual specimens in a 100-meter section.

They also host predators that predate aphids, small sap-sucking insects, which are getting harder to control in commercial crops, and seem to have reduced pests that would attack the onion crops.